Thoughts on the Sonnet from Maine Poets

We asked Maine poets: “What are your thoughts on the sonnet? As a writer? As a reader? Do you love the sonnet form, revel in it, respect it, hate it, or is it complicated? What are the risks and rewards of the sonnet for poets today?”

We heard from prizewinners and laureates and from young poets just beginning to write. Here are their thoughts.

“I am obsessed with writing sonnets—I write one every morning. I think my obsession is rooted in my belief that the sonnet mimics the way we think through things: a tangled and beautiful puzzle of the “There’s this” of the first stanza, and the “And also this” of the second stanza, and then the delicious “But then there’s that” of the volta, and I know I crave the kind of closure on an argument with myself that the couplet can give. So, in this way, my daily sonnets are a sort of journal of whatever thoughts I am wrestling with first thing each day.”

—Meghan Sterling, author of View From A Borrowed Field

“The sonnet means to me a more flexible room than what's been originally taught to us. A sonnet is an opportunity for a cozy poetic room.”

—Maya Williams, author of What's So Wrong With a Pity Party Anyway?

“My favorite kind of poem is what the American poet Carl Dennis calls “the poem of mid-course correction” in Poetry as Persuasion, which is a great book that had a huge influence on me when it came out. This kind of poem turns while it moves, like the double helix of our DNA. Such poems are not new—certain very old Japanese haiku can be said to move in this way, if only just a very tiny bit. The sonnet is the master of these turns, by which I mean that the poet’s argument can be said to spiral first into the octave and out of that into the sestet and out of that into the concluding couplet. The miracle of all this spinning is that, like other things in nature, it holds together while falling apart. Linguistic turns help us to say more than one thing at a time. That is, they help us to embody a contradiction, which is what poetry does best. I also very much love in poetry its ability to surprise us. For this reason, though I admire older sonnets, I am always more interested in and more moved by the more rebellious ones. The punkish and insubordinate ones. The rowdy and impetuous ones. Olena Kalytiak Davis’s shattered sonnets is a great example. Also Diane Seuss’s frank: sonnets and Terrence Hayes’s American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin. Oh, and Gerald Stern’s American Sonnets. He’s the true American king of the voice-driven poem of the insubordinate turn into what that great American poet Billy Ray Cyrus calls the “achy breaky heart,” though all of these books are little miracles, and everyone should read them.”

—Adrian Blevins, author of Status Pending

“With a sonnet, it’s like, let the game begin! You got 14 lines and 140 syllables to make some sense! I like having a lot of options eliminated, it’s like making a meal but all you have is fire, a knife and what’s ripe in the garden. Maybe salt, too. It's cool what that iambic pentameter does in a sonnet . . . when read aloud it’s as if there’s faint music or a drum backing the voice. Read it with a friend on guitar and it’s something else again, you’ve got words/meaning/rhythm/voice/chords. I have to stretch my vocabulary to pull off a sonnet, which usually means it’s less boring to the reader. And I like finding long words with good meter, or a line where the meter is hidden because it crosses words. Rhymes can be hidden too. And I like it when a listener is surprised that what I’ve read is a sonnet.”

I mostly stick with Shakespearean sonnet form, and it's doing all I want it to so far. The rules are simple, and with those rules an awful lot of choices are eliminated. It’s like if you go to make a spoon and power tools are not an option. I don’t need more choices! The form of a Shakespearean sonnet is like a mold: pour in the syllables, accents, and rhyme and have something to say. Writing a sonnet is as close as I’m ever going to get to shaking William Shakespeare’s hand, or maybe just waving to him, even if he doesn’t see me. Writing a Shakespearean sonnet is like dressing my poem in a Harris Tweed jacket, with a tie on. It has to be comfortable, in my voice, while following an Elizabethan-era norm. Kind of tricky.”

—Peter Beckford, winner of the Belfast Poetry Festival’s 1st annual Haiku Death Match

“I love sonnets because I think of them as expandable little boxes. Sort of accordion boxes, little song boxes in which I can do whatever I’d like, and then make sure things line up into the fourteen lines, and that fourteen-line magic is like dressing the poem up in a tuxedo—classic style, never out of fashion, even if the contents aren’t very classic. I also enjoy sonnets for their imbalance, their momentum, how there’s an inherent tipping or slope between the octave and the sestet, how it’s like watching water flow down through a ditch in the octave, and when the water hits the sestet, it’s like the water enters the culvert and—whoooosh—the poem streams away to the open ocean.”

—Jefferson Navicky is the author of Head of Island Beautification for the Rural Outlands

“A little later, I discovered the sonnets of Edwin Denby, who was devoted to them throughout his life. Some rhymes remained, like pentimenti, and there was intense compression of thought and syntax. Alice Notley published sonnets as well. I wrote a sonnet sequence when I was about 20 and dedicated it to Alice. To me, the sonnet was a way of moving through space, time also, of course, but space seemed more urgent. You could get somewhere important in 14 lines. Most recently, I’ve devoted myself to reading all Shakespeare’s sonnets. I read them slowly, intensively, with the notes. Then, I sit at my table and look out the window and try to write a poem about the weather on that particular day. It usually takes me more than one day, and I like how the poem can stretch from day to day, and from weather to weather. I enjoy Shakespeare’s sonnets because they have an obsessive drive. The sequence structure allows him to obsess about love, evolving his concern, particularly about one person, as the unit turns into a large, twisting snake of sound and image.”

—Vincent Katz’s most recent book is Daffodil and Other Poems

“I’ve been arguing with the rigor of the sonnet form, both English and Italian styles, since I took a creative writing class in college where we spent the first two weeks writing sonnets with a twist. Our sonnets had to add something new to the traditional forms. That’s when I discovered Millay’s modern sonnets not only moaned and groaned about lost love, but they also kept the emotional turmoil of her life somewhat at bay. Her sonnets which have stunned me most are in her poem sequence depicting a woman who left her husband but has now returned to watch over him, somewhat unwillingly, as he is dying. As in many of her sonnets, Millay’s lifelong project seems to have been an ongoing effort to create space for a woman’s voice. Cleverly, my professor followed up Millay with Adrienne Rich, and we immediately saw how both poets were bent on exposing how the individual and collective voice of women has been suppressed.

P.S. These days, I am finishing up a manuscript called Sonnets, Interrupted, in which the poems are all thirteen lines.

These are the lines I often go back to in Millay’s “Sonnets from an Ungrafted Tree,” in which the speaking voice of the woman looks back on her difficult married life:”

from I

"So she came back into his house again

And watched beside his bed until he died,

Loving him not at all.

(ll. 1-3)

from XI

"It struck her, as she pulled and pried and tore,

That here was spring, and the whole year to be lived through once more.

(ll.13-14)

from XVII

"And sees a man she never saw before—

The man who eats his victuals at her side,

Small, and absurd, and hers: for once, not hers, unclassified." (ll. 12-14)

—Kathleen Ellis’s most recent collection is Body of Evidence. She teaches poetry and creative writing at the University of Maine, Orono.

“While I don’t write a lot of sonnets myself, what strikes me about the form is just how personal it is. All poetry requires a degree of vulnerability, but I feel as though in sonnets, the poet is truly baring their soul for the reader to see. Also, I tend to enjoy poetry that’s very well-structured, and sonnets certainly fit that definition.”

—Len Harrison, Brunswick, finalist for the 2025 Maine Literary Award for Youth Poetry

“Reading Gwendolyn Brooks’s astonishing sonnet, my dreams, my works, must wait till after hell, is my poetry origin story. Encountering this ingenious poem as a young waitress determined me to become a poet. Her sonnet plays the form to perfection: conjuring a pantry, the speaker creates a room that is pure, orderly, beautiful, as an antidote to hell. In this world, hell often comes first. The sonnet, as Brooks creates it, is poetry’s answer to hell. I myself write very few sonnets and when I use the form it is to hold a place of return for the unspeakable.”

—Claire Millikin, author of Magicicada

“The sonnet form is intimidating to many writers because of its detailed rhyming and metric structure. But I like to think of the structure as a stylistic benefit for the writer as well as a challenge. For example, writers can use iambic pentameter to enhance emotion, breaking or changing the rhythm in specific places for emphasis. And synchronizing words with the form of the poem can also draw attention to them, like using the ending couplet to highlight a key theme of the poem. It’s hard to do, but when done well, the rhythm and structure of the sonnet form adds depth to a poem in a way the words alone couldn’t, almost like how the melody of a song adds to the lyrics.”

—Lily Jessen, eleventh grader from Cape Elizabeth Winner of The Telling Room’s 2024 Statewide Writing Contest & Author of The Pipe Tree

“Poem of eras, dotted between plays

Books and romance, speckled between stars

Performed in a sunny, bantering craze

Or deep, a lament formed by the heart’s scars

Sonnet is anything, riddle, question

Ticking in the womb of the poet’s mind

String caught between world and soul, in tension

Until history must let it unwind

Yet sonnet, with its fragile fine form

Light and whimsical, a floating magpie

Builds mountains from fragments dusty and worn

Uproots ideals and makes the cruelest cry

Weapon of warriors, using pen as shield

Shape shifting, light, airy, yet cold and steeled”

—Denali Garson, eighth grader from West Gardiner, The Telling Room’s 2024 Statewide Writing Contest Kennebec County Winner

“Lately I’ve been taking a deep dive into Edna St. Vincent Millay’s life and work, reading five books concurrently: two biographies, a book of her poems, a book of her letters, and a book of her journals/diaries. I’ve never done anything like this before and it’s exciting! At the same time, I’ve also begun memorizing some of her sonnets. I love the way the language and rhythms seep into my brain. Plus I’ve gained a new appreciation for her word choice. My current favorite is

“Love is Not All.” That floating spar even made it into one of my own recent poems which ends like this:

In this life accented with grief, I keep hold of you

like a floating spar as I’m dragged through mud and silt and seaweed into the raging ocean of life alone.”

—Judy Kaber, author of A Pandemic Alphabet

‘Thou art indeed just, Lord, if I contend’

by Gerard Manley Hopkins

Justus quidem tu es, Domine, si disputem tecum; verumtamen

justa loquar ad te: Quare via impiorum prosperatur? &c.

Thou art indeed just, Lord, if I contend

With thee; but, sir, so what I plead is just.

Why do sinners’ ways prosper? and why must

Disappointment all I endeavour end?

Wert thou my enemy, O thou my friend,

How wouldst thou worse, I wonder, than thou dost

Defeat, thwart me? Oh, the sots and thralls of lust

Do in spare hours more thrive than I that spend,

Sir, life upon thy cause. See, banks and brakes

Now, leavèd how thick! lacèd they are again

With fretty chervil, look, and fresh wind shakes

Them; birds build—but not I build; no, but strain,

Time’s eunuch, and not breed one work that wakes.

Mine, O thou lord of life, send my roots rain.

{Poet Betsy Sholl rarely writes sonnets herself, but she’s long been fascinated with this sonnet by Gerard Manley Hopkins.}

“Everything in this beautiful sonnet is paced to create a mix of argument and grief.

There is the direct address reminding us this is prayer and a complaint with a specific addressee. There are wonderful ironies like, “Wert thou my enemy, O thou my friend . . .…” Hopkins is a master of syntax, as when he holds off the verb in his question, “why must disappointment all I endeavor end?” I think the turn comes when Hopkins introduces the spring growth and breeding birds, shifting the poem from complaint to plea, presenting the evidence and upping his argument. It’s remarkable how many one syllable words there are in this poem. After briefly giving us leavèd, lacèd and fretty chervil, Hopkins goes back to those heavily accented and plaintive monosyllables in the last lines: “birds build—but not I build.” And then the closing line’s impassioned prayer: “Mine, O thou lord of life, send my roots rain.” Read that with nearly every word accented, and the passion is palpable.”

—Betsy Sholl’s latest book is As If This Song Could Save You.

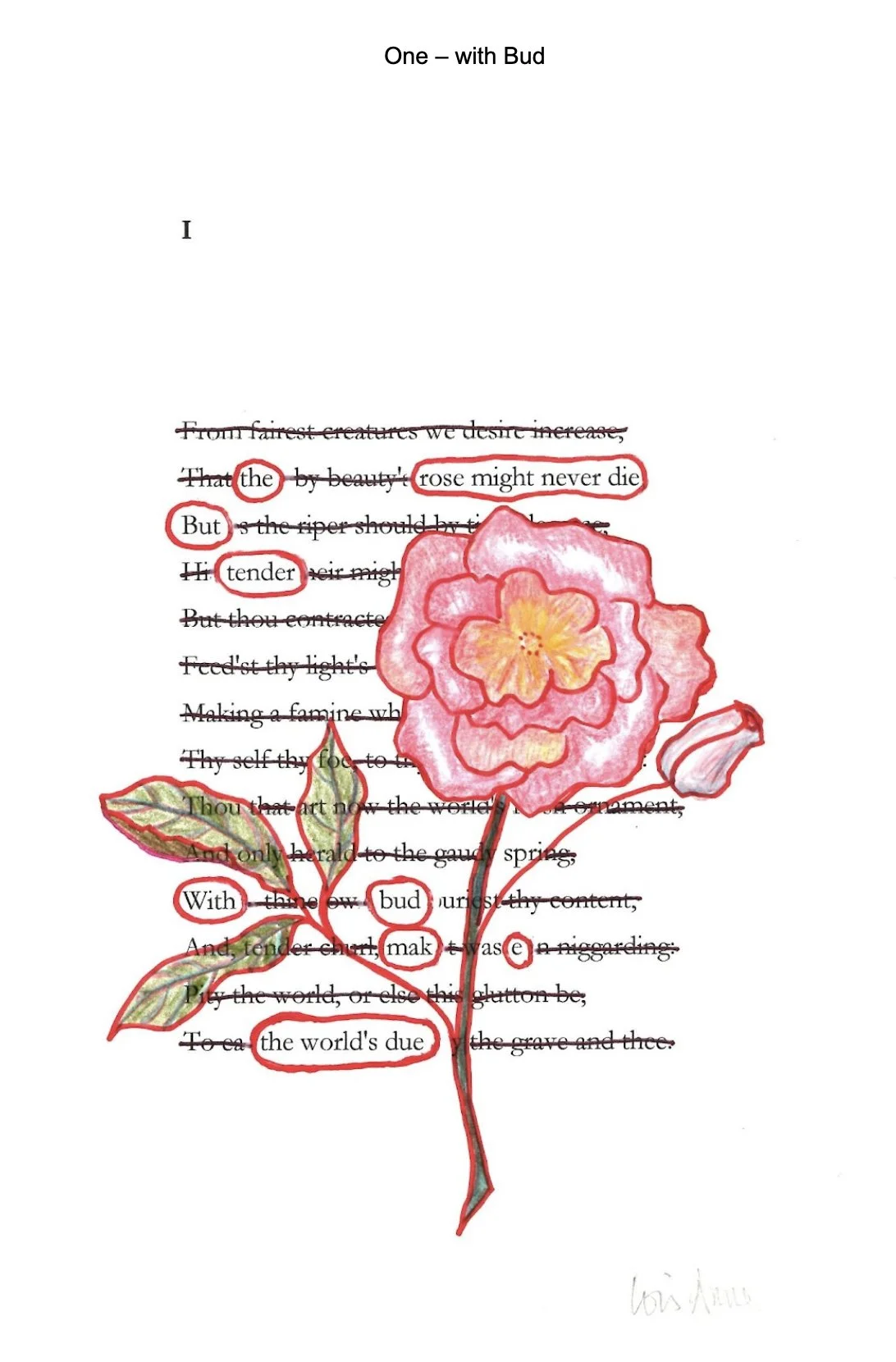

“One – with Bud,” an erasure poem, uses Shakespeare’s first sonnet as the source text. Erasure poetry is a form of poetry wherein a poet takes an existing text and erases, blacks out, or otherwise obscures a large portion of the original text, thereby creating a wholly new work from what remains. For Millay House Rockland I could have selected one of Vincent’s sonnets, but since women have been erased throughout history, I intentionally do not do erasures of women’s work.

—Lois Anne, an artist, poet, and visual artist who has maintained a studio in downtown Rockland since 1984.