Two Poets Encountering Charles Simic

Bill Schulz and Mike Bove

The Night Charlie Simic Couldn't Find The Words

Bill Schulz

Charlie’s office at the University of New Hampshire was at the top of the stairs in Hamilton Smith Hall. And when I first climbed those stairs nearly 50 years ago, I had no idea who or what I would find. He was, even then, a major poet. Meeting Charlie for the first time was like sitting next to Carl Yastrzemski in the Red Sox dugout.

I’d read and was in awe of two of his early books Dismantling The Silence and Return To A Place Lit By A Glass Of Milk. The poems there broke open my idea of what poetry could be. Who has the nerve to end a book with a poem titled errata with lines like:

Where it says knife read

you passed through my bones

like a police whistle

or:

Remove all periods

They are scars made by words

I couldn't bring myself to say

I half expected to meet a skinny guy dressed in black or a dark, Slavic prophet.

No. I met Charlie—kind, funny, Cubs fan. He let me in.

First things I noticed: he was missing the tip of an index finger; he smoked skinny brown cigarettes he got from an obscure tobacco shop; he had a great laugh.

Our poetry group was small, just seven or eight people. I believe he pulled us together in a kind of literary science project—put a militant feminist, a southerner with a degree in biology,* a Brit, a SoCal woman, a sprinkling of other eccentrics in a small room together, add cheap wine and cigarettes, and see what happens.

Oh, and me—the tall guy. At the time, I was trying to translate ancient Chinese poems without knowing any Chinese language.

It was all a great challenge to get a good review from Charlie. He was generous with his response even when the work was truly bad. I turned in more than my share of forced, clunky, intentionally obscure work only to get a laugh and a "Schulz…" sigh.

We spent time together in and out of the classroom. Once we invited the fiction students to join us for one of our salons. They all stood or sat on the perimeter gathering material for their short stories.

In the 40 years I knew him, Charlie was never at a loss for words.

He invited me to his house a week or two before I returned to the world. After a wonderful dinner we retreated to his study where he gave me two parting gifts. The first was advice. I asked him what I should do next. I was about to move to teach at a private school in North Carolina and planned to get into a doctoral program in a year or two. He told me to "Go home, live a good life, and just write." (I didn't listen.)

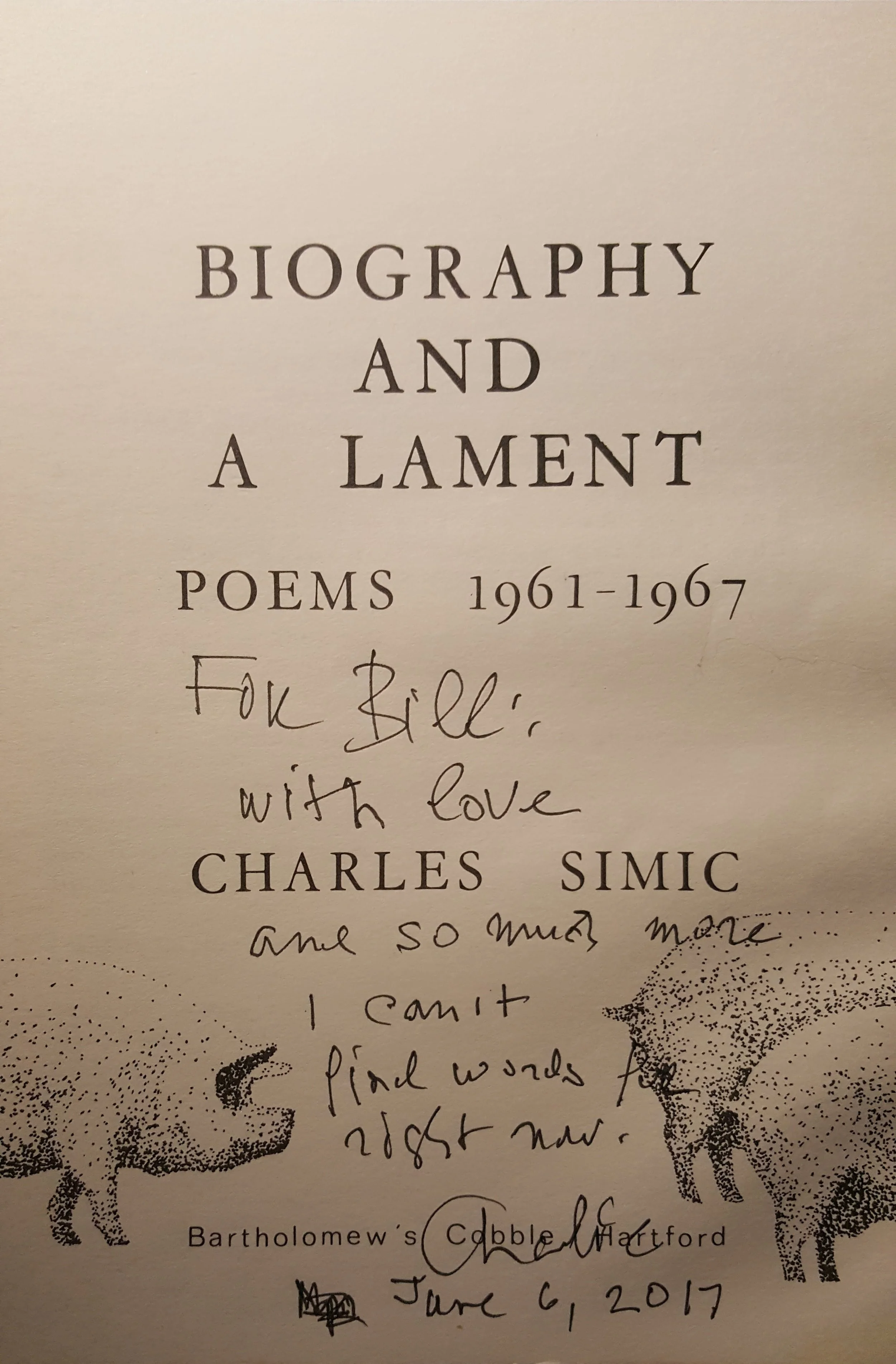

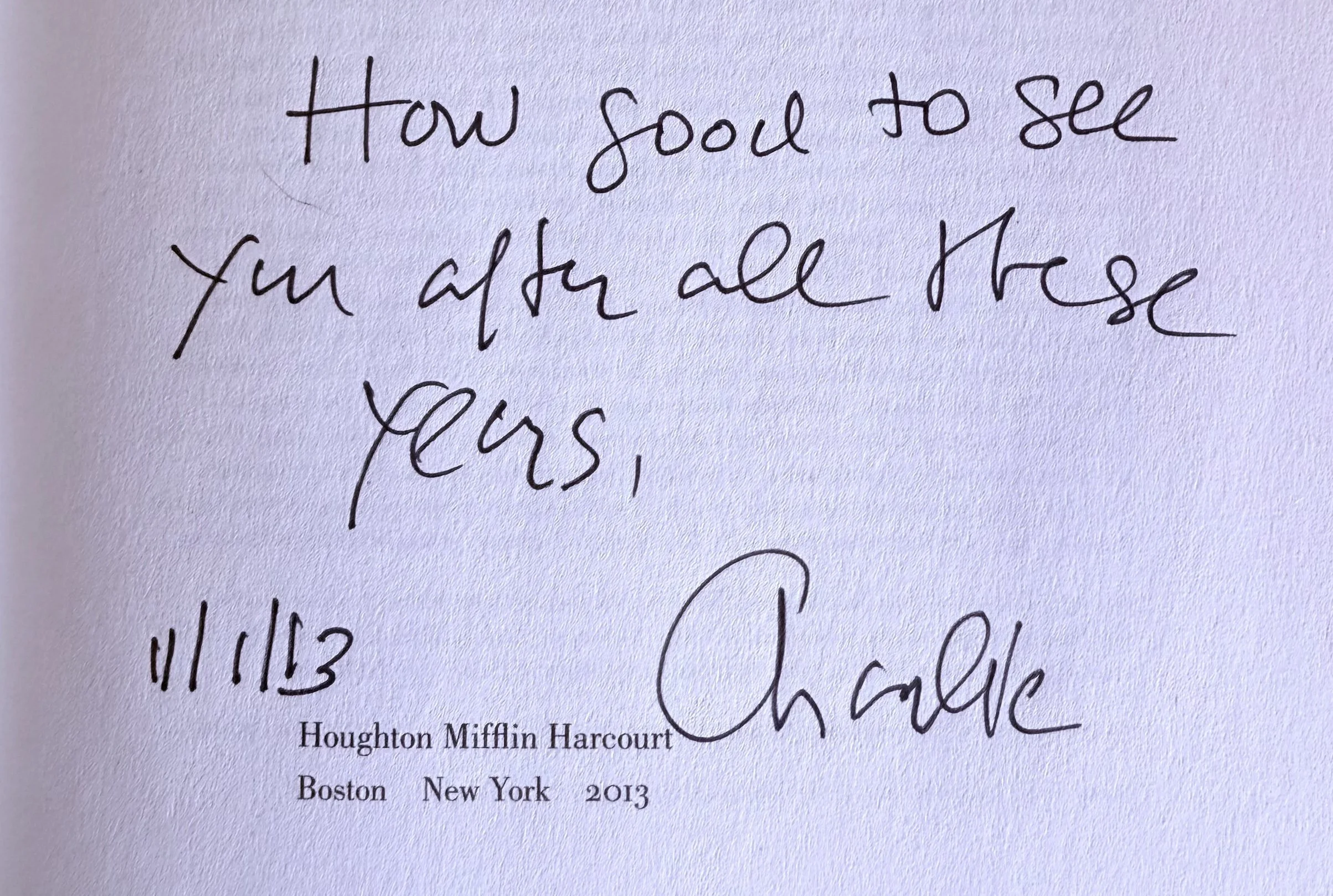

The other gift was a copy of a small limited-run book of his, Biography And Lament. Just 10 poems, 10 exquisite poems that speak to his childhood during the time of war in Yugoslavia and early times in the States. I believe the 10 poems are among the most moving poems he ever wrote.

We stayed in touch over the years. I'd go to a reading when I could, including one memorable reading he did with Mark Strand. After the reading, Charlie invited me to join them in the blue room. Strand had a bottle of wine, exquisite and expensive (of course), but no corkscrew. Charlie took out a pen and, to Strand's horror, poked the cork down into the bottle. We finished the bottle picking small bits of cork out of the wine.

The last time I saw Charlie was at a reading he gave at a small jazz club in Portland, Maine. We ate dinner together along with Helen, his wife and constant, beloved companion. People stopped by the table to speak with him and/or bring books for him to sign, which he did without hesitation.

I don't recall why but I'd brought my copy of Biography And Lament with me to be signed.

This is what he wrote:

*Charlie told me a story of Frank, this poet who wrote mad, unintelligible poems about DNA. After he'd finished the program Frank took buses deep into Mexico. A year or so later he'd shown up in Charlie's office with a gift of a shrunken head. Horrified, and with as much kindness as he could muster, he told Frank he just couldn't accept it.

Six Sketches of Simic

Mike Bove

1.

I didn’t know Charles Simic well, but well enough to know he didn’t like posturing or pretense. Students called him Charlie. He wore rumpled sweaters and worn shoes. In the classroom, he held himself like your best friend’s dad: kind, comfortable, quiet. Approachable. Spending even a little time with him gave the sense that he valued character over showiness, heart over ego.

2.

He was one of the funniest and smartest people I’ve ever met, though his style was understated and idiosyncratic, not for everyone. Some students hadn’t heard of him before taking his class. One day the student next to me said, “I Googled him last night. There were like a million results. I don’t get it.”

3.

He relished a good story. The funnier the better. In a discussion about humor’s place beside the tragic, he described a burial he’d recently attended. It was somber, raining. People wept. From the corner of his eye, he saw a bright spot bouncing at the edge of the cemetery, growing larger, moving quickly toward the mourners. He recognized it as a yellow lab puppy. No one else yet saw. He stood very still, watching with delight as it bounded toward them, drunk with tongue-wagging-goofiness, and leapt directly into the open grave.

4.

I kept my notebooks from my time as his student. In them, I scrawled insights he’d casually drop during class. My favorite: Imagination doesn’t create. It sees connections to what’s already there.

5.

He loved Emily Dickinson. On the blackboard, he drew a chart of her creative output, writing the number of poems she was supposed to have written during each year. 366 poems in 1862. He circled it. Twice. “Imagine this!”, he said. He was blown away. It was like he was learning it at the same time we were.

6.

Once at a reading, I saw a young fan ask him how winning the Pulitzer changed his life. He shrugged and said, “We could afford to get the kids braces.”

Bill Schulz lives in Maine, not far from the farm where his ancestors settled in the late 1780s. He received a master’s degree from the poetry program at The University of New Hampshire in 1976 and a master’s in theological studies from The Franciscan School of Theology in Berkeley, CA 30 years later. His book of poetry, Dog or Wolf, was published by Nine Mile Press in 2022. His second book, Another Psalm, was published in 2025 by Kelsay Books. He is the founder of Hole in the Head Review.

Mike Bove is the author of five poetry collections including Mineralia, forthcoming from Cornerstone Press at the University of Wisconsin Stevens Point. He lives in Portland, where he was born and raised.