What’s a Singhi Double House?

Adapted from the work of Ann Morris, Rockland Historian and MHR board member, and her research on the significance of the Singhi Double Cottage for the National Register of Historic Places.

It may surprise members of the Millay House Rockland community to learn that the residential structure at 198-200 Broadway gained the honor of its listing on the National Register of Historic Places not because the first women to win a Pulitzer Prize for her poetry was born under its roof but for its significance as an outstanding surviving example of vernacular working-class housing stock from the time when Rockland was a gritty and sooty hub of lime-burning, shipbuilding, and fishing.

By the end of the 19th century, rusticators and artists had discovered the Maine coast, but chances are most of these Gilded Age tourists weren’t disembarking from their steam packet in Rockland, preferring instead to enjoy cigars in onboard saloons as they awaited fresher prospects further downeast, like Mount Desert Island, or at least up the Bay to Camden. Rockland wouldn’t have been an inviting stop, its waterfront grimy and hectic with the work of the lime industry, dozens of kilns constantly ablaze, rail lines shuttling stone from the quarries, schooners being loaded dockside, coopers, wrights and laborers of all sorts sweating their trades. Vacationland it wasn’t. It couldn’t even be called quaint.

Tourists might not be welcome, but workers were certainly needed for all this industry, which included Rockland’s shipyards and fisheries as well, lots of workers, who at first were put up in boarding houses, like the one that Edward Hopper would eventually paint as a “Haunted House” in the 1920s. But as the men in these jobs had families and settled into the community, finding suitable affordable housing become a concern.

In Rockland, a pattern of building double houses developed. These modest houses could economize on lot-size and construction, since you would have two dwellings joined along a common wall, under one roof, each side a mirror image of the other, and each side owned separately.

In time, double houses became a signature housing style of working-class Rockland, with at least 125 being built in the residential neighborhood east of Broadway, a prime location for the expansion of affordable housing as the growing city’s settlement pattern pushed out from its working waterfront. 70 of these houses remain standing today, more than any other city or town in Maine.

But what’s a Singhi double house?

Businessman Wellington Singhi, whose mother built the Singhi block on Main Street, Rockland, acquired land on Broadway and built single family houses on speculation and for rental income in the 1880s. These well-built but modest dwellings were soon being called the Singhi Cottages.

Singhi built one double house at 198-200 Broadway. It has particularly well-preserved Queen Anne stylings, including various patterned shingles on the upper story clapboards and decorative pediments supported by carved brackets associated with its protruding gables, and the interior retains its original period woodwork with bullseye designs. The Singhi Double Cottage uniquely maintains the character of dwellings built for the working-class Rockland at the turn of the 20th century, and it would be architecturally and historically significant, today as a fine example of a double house, even if Wellington Singhi hadn’t rented the north side of the cottage to Henry Tolman Millay and his wife Cora soon after it was built in 1891.

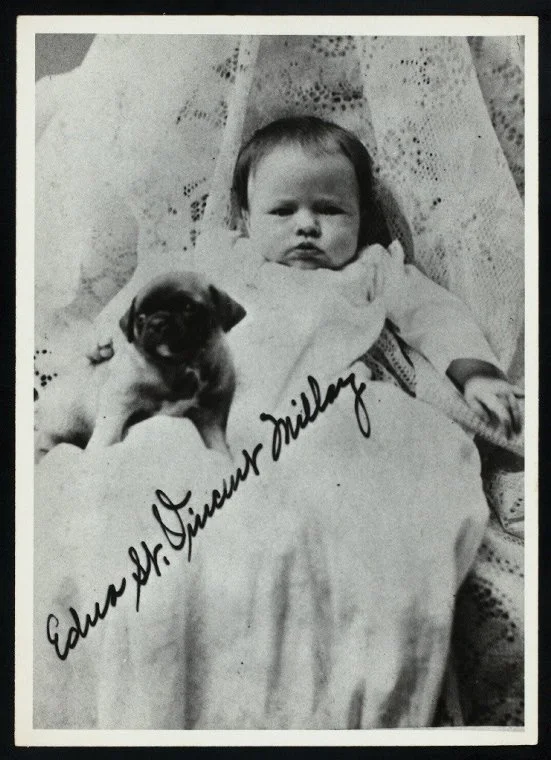

In February 1892, Edna St. Vincent Millay was born on that north side of a Singhi double house in Rockland, Maine. She only got to spend her infancy in the house, but one’s birthplace marks the first record of everyone’s personal history, even if history takes them far from the grit, salt and sweat of a busy, working-class seaport.

History has taken Rockland some distance as well from the days of the lime industry and the city’s shipbuilding past. There’s still a working waterfront, and the place wears proudly its working-class vibe. Rockland is still a top-five port for the amount of commercial seafood landed in Maine, and Knox county overall tops the state in the value of its catch.

But there’s no doubt that the tourists now stop in Rockland, as well as the artists, as they have been increasingly throughout the last century. The last handful of kilns went cold in the ‘50s, and no last grit of limestone is coming out of the quarry in Thomaston now that the cement plant is winding down its processing work. The city is now written up for its arts and foodie scene (but it still has a desperate need for affordable housing).

Millay, of course, never really left Rockland and midcoast Maine. The place is an integral part of her psyche, which you can note in poems like “Exiled,” with its longing to hear the gulls cry and the wooden piles of a pier groan against the waves. And there’s a part of Millay that’s still in Rockland, Maine. It’s what makes the rough houses turn lyrical, and the small human details of workaday life stand out as poetry, all of which, in their honesty, is the art of endurance, more durable than any tourist’s souvenir.