Almost There: Unexpected Thresholds of Revelation

Lucia Graves on Emily Dickinson and Edna St. Vincent Millay

© Dickinson Homestead Museum

There’s a strain of literary thought that dismisses the physical contexts of writers’ lives as trivial—houses, landscapes, objects, scraps of the larger beauty that shaped them. Genius, the argument goes, lives in the work alone: it’s right there on the page and not in the ephemera they left behind or the spaces they inhabited. It's an intellectually tempting argument, the purity of the written word. But the more time I’ve spent with certain poets—Emily Dickinson and Edna St. Vincent Millay chief among them—the more clearly I’ve seen the limits of that view.

This was recently underscored for me at a Millay House event in Rockland this fall, when the poet Rosa Lane spoke of all the ways Dickinson's queer life had been written out of the record, the very name of the woman she loved scraped from the manuscripts. Dickinson’s queerness, like so much we know about her, survives not in the poems that reached print only after her death, but in the margins—literally and metaphorically: the small, accidental traces she left in letters to friends or jokes made to a sibling.

I’ve come to see this too with Millay. She's a poet I’ve loved on the page since adolescence, long before I ever set foot in Maine, but coming to live in the Midcoast these past few years—where she was born and raised—has changed how I read her. What once felt powered purely by imagination now seems inseparable from the landscape she drew from—the wind off the harbor, the abrupt rise of the hills, the cliff's edge where mortality feels suddenly near. Here, her poems feel less invented than translated, as if she were giving voice to something the land already knew. I sometimes catch myself lingering over a line—“watch the wind bow down the grass,” or “the drenched and dripping apple-trees”—and wondering if she was standing somewhere near this very place when she wrote it. It has made me think, more than once, that a poet’s genius is never wholly theirs. It’s shaped by the ground they walk, the atmosphere that carries them, the world that imprints itself on their imagination.

With Dickinson, one of my strongest connections to her came not through a poem she wrote, but a song she heard. Not even a song I know she played herself—but one I first encountered in the archives of her correspondence.

The tune surfaces in an 1851 letter Dickinson wrote to her brother, Austin, where she offers a dry report of an evening spent at home with her cousin, Lavinia—known as Vinnie:

“We are enjoying this evening what is called a ‘northeast storm.’ … Vinnie is at the instrument, humming a pensive air concerning a young lady who thought she was ‘almost there.’ Vinnie seems much grieved, and I really suppose I ought to betake myself to weeping; I’m pretty sure that I shall if she don’t abate her singing.”

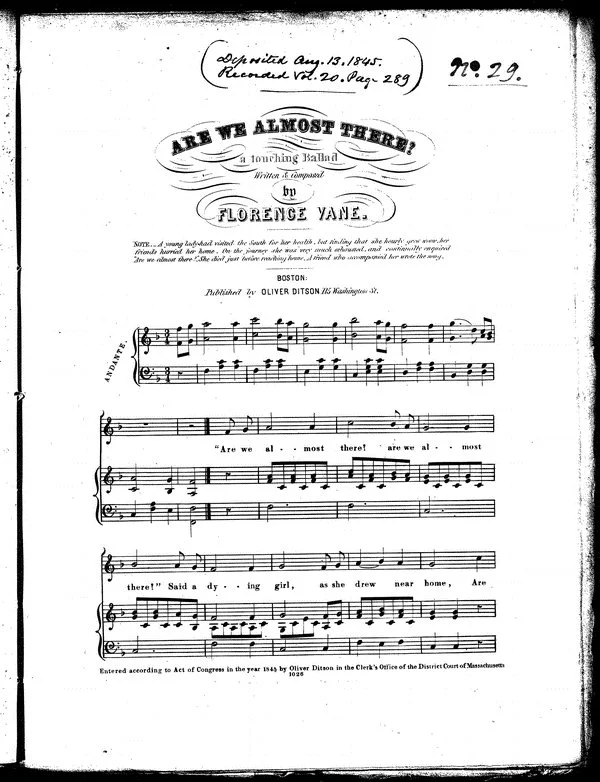

The song she’s thought to be referencing was “Are We Almost There?” As a note on the original score explains: “A young lady had visited the South for her health, but finding that she hourly grew worse, her friends hurried her home. On the journey, she continually enquired, ‘Are we almost there?’ She died just before reaching home.”

The tune had surfaced earlier in Dickinson’s life. In an 1846 letter to her childhood friend Abiah Root—her Amherst Academy classmate and one of the correspondents she confided in most—Dickinson asks after the song with real interest: “Have you seen a beautiful piece of poetry which has been going through the papers lately? ‘Are we almost there?’ is the title of it.” Five years before the joking complaint, the refrain was already lodged in her ear, refusing to let her go.

I learned the tune on the piano for a final project in a comparative literature course many years ago. Like most of college, the sharp edges of my memory are gone and I don’t remember exactly why I chose to learn it—only that it captivated me. When I played a recording of myself singing and playing it for the class, I vividly remember how strangely and beautifully it landed—how people were moved. My voice on those notes, my fingers on those keys, falling on other people’s ears more than 150 years after that song fell on hers, became a small conduit into Dickinson’s interior world. I watched the room shift—students leaning in, as if something in her had quickened.

The tune stayed with me—just as it stayed with Dickinson, I like to think—and over the years it sharpened my attention to a theme she returns to again and again in her poetry: the moment just before arrival, the breath held at a threshold.

© Dickinson Homestead Museum

Dickinson was after all, in many ways, a poet of almostness—of scenes suspended one inch shy of revelation or completion or eclipse. In poem after poem the world is not transformed but about to be: “A Plank in Reason, broke—”; “adjusted in the Tomb”; “stepped straight through the Firmament / And rested on a Beam—.” Her speakers stand at windows, bedsides, dawn’s edge, hovering in that charged pause before the thing happens. The dying girl in the parlor song begging “Are we almost there?” belongs uncannily to the same emotional register. Fingering that melody, mouthing along, half outside myself, I felt I’d stepped into Dickinson’s favored terrain: the liminal moment where nothing is complete and everything vibrates with the nearness of change.

Maybe that’s why the music felt like a true doorway—not for what it explained, but for where it allowed me to stand: inside her vocabulary of thresholds. Playing it, I could feel the tug she so often wrote about: a consciousness leaning forward, “shivered scarce,” the soul “upon the window pane,” close enough to touch but held back by some invisible scruple or fear or awe.

At the event in Rockland this fall, hearing how Susan—the woman Dickinson loved—had been systematically scrubbed from the published record, I was thunderstruck by the irony. Even Dickinson’s ferocious poetic purity—her refusal to be published at all if it meant being “improved” by lesser editors in any way, her fury at a single changed or removed word—couldn’t protect her from what history would do. In fact, publication with minor impurities may have kept her from an even greater erasure. The world still reached in, anyway, in the seemingly benign hands of the people who loved her and outlived her—editing, softening, straightening, erasing—but also, paradoxically, preserving the only records that let us understand what we do. Were it up to Dickinson and her unwavering artistic purity, everything would be burned.

I suppose I must thank God that the flawed forces of publication prevailed, even as they’re a testament to why we can’t rely solely on the written record. The poems themselves, gorgeous as they are, don’t always tell the whole truth.

I feel that with Millay, too—recognizing her in this landscape, and this landscape in her—it’s as if I’ve been connected, even fleetingly, with the muse she pinned so ingeniously to the page.

If I find Millay in the vistas and valleys of the Midcoast, I find Dickinson in witty correspondence—and in the tune that hovers just ahead, just behind—almost there, almost lost—exactly the way she wrote: at the brink of unknowable revelation, bright as the light under a door.

Lucia Graves is a writer and journalist based in Midcoast Maine, where she lives with a dog, a cat, a husband, and a kindergartner—not necessarily in that order. She wrote about Millay and “The Hunt for Maine’s Most Poetic Vista” in the Midcoast Villager 2025 Summer Guide.